Memory Cache Hub

Author: John Shaughnessy

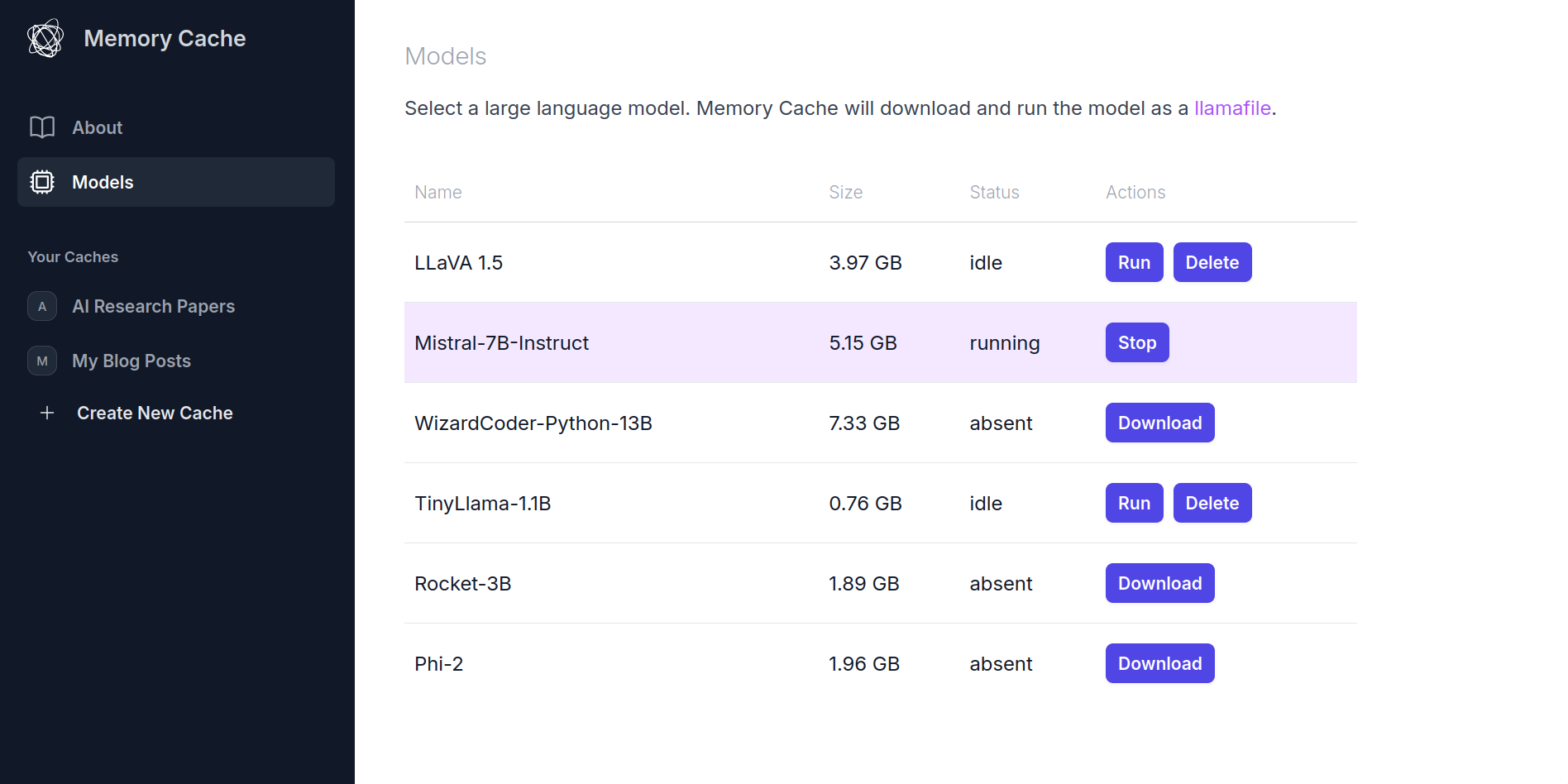

Memory Cache Hub

In a dev log last month, I explained why we were building Memory Cache Hub. We wanted:

- our own backend to learn about and play around with

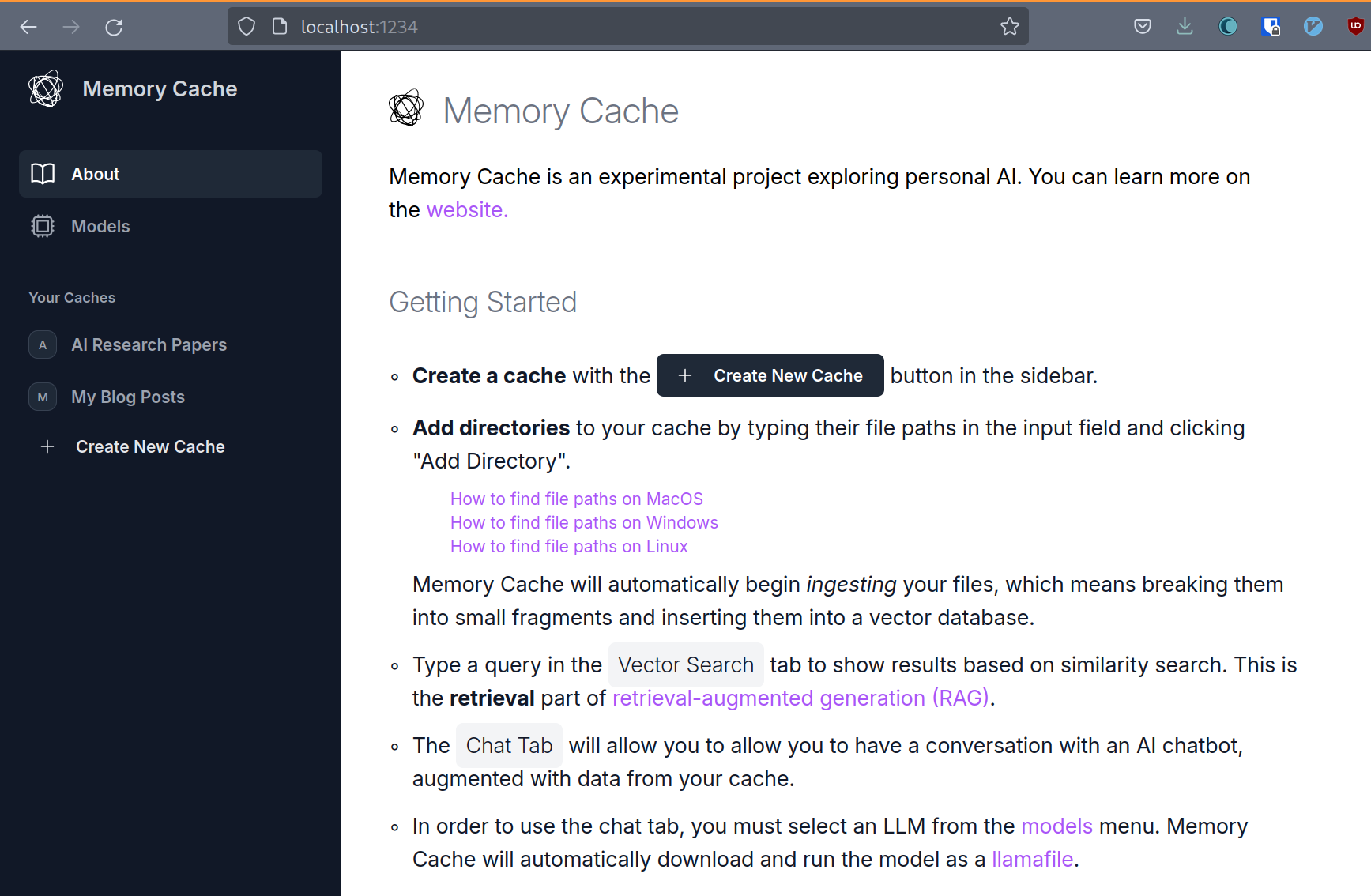

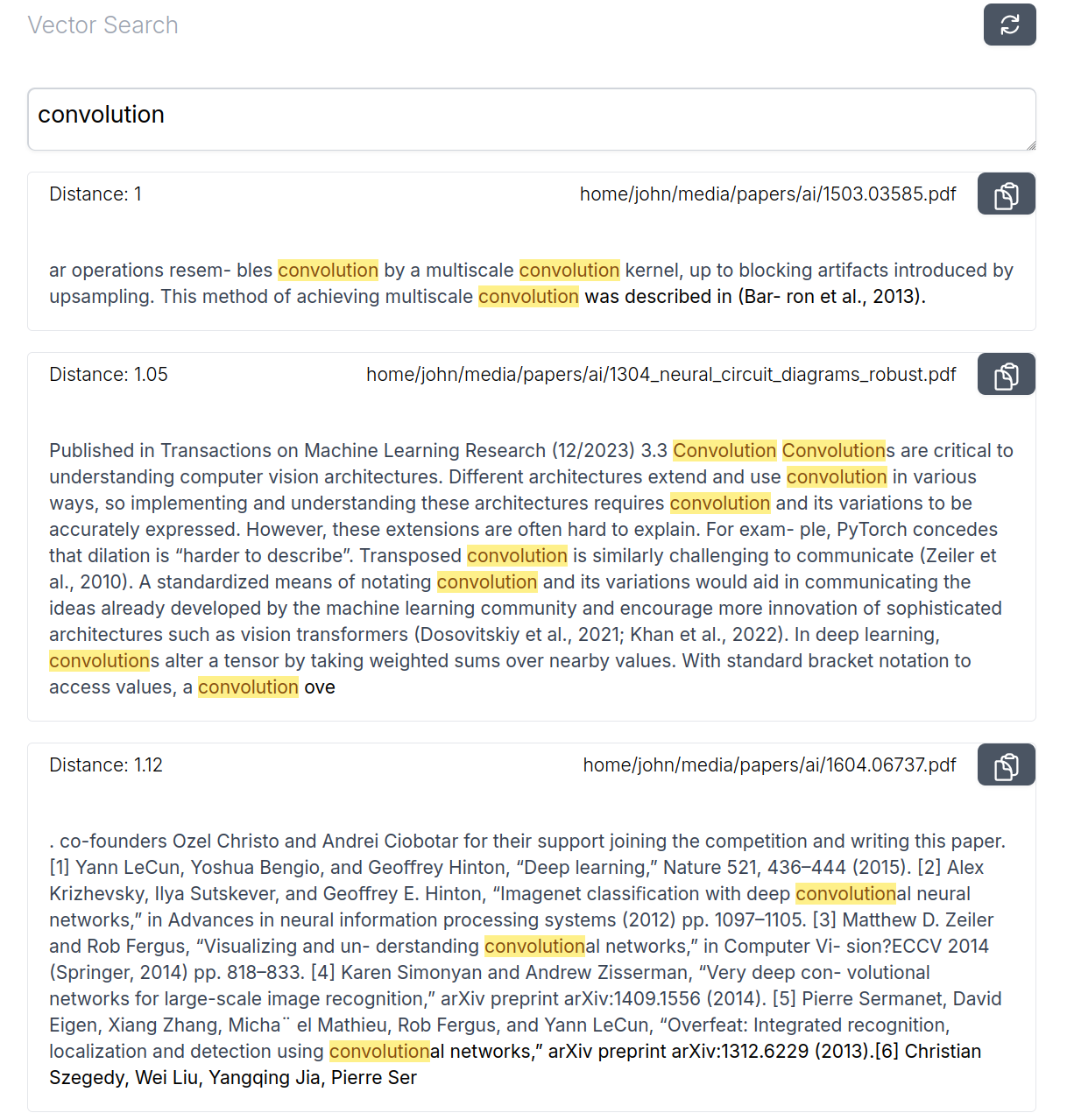

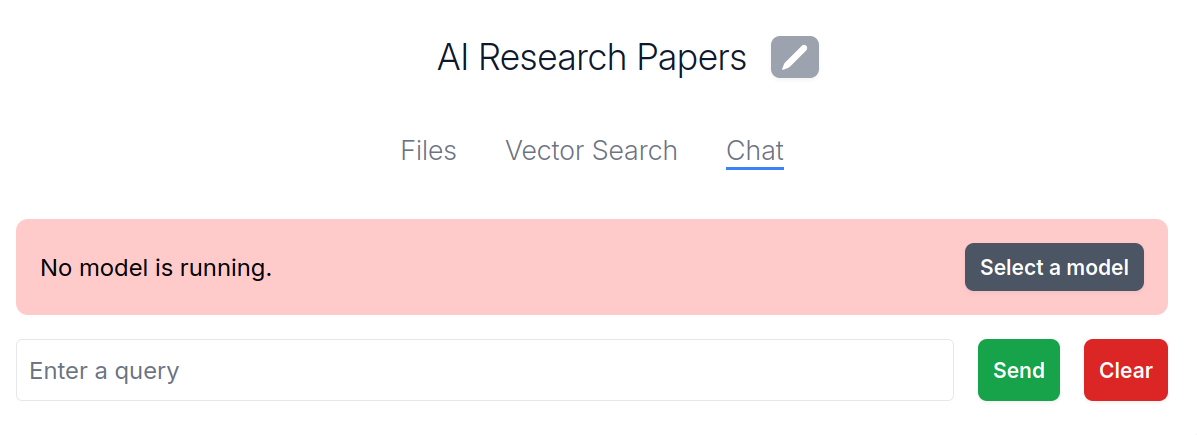

RAG, - a friendly browser-based UI,

- to experiment with

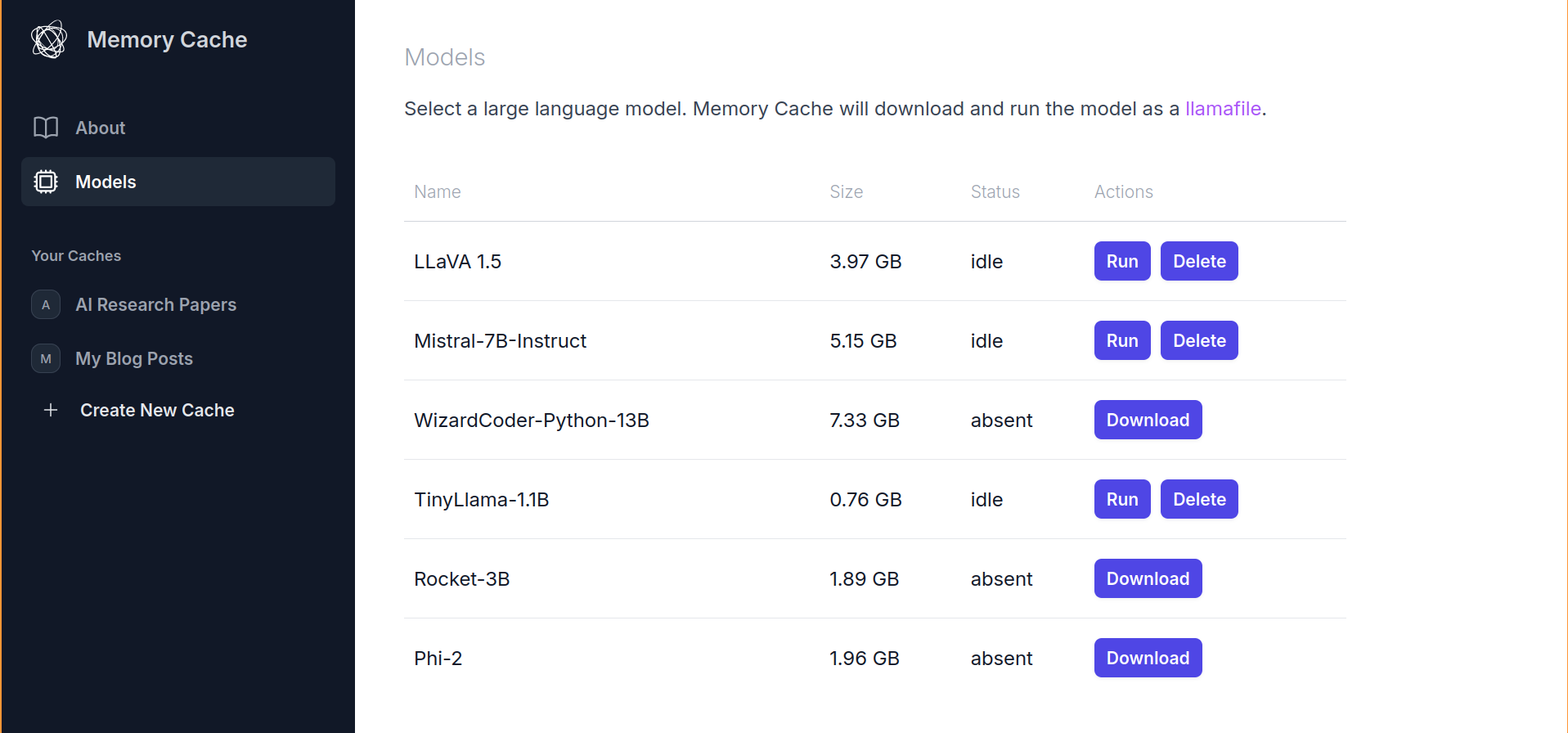

llamafiles, - to experiment with bundling python files with

PyInstaller

The work outlined in that blog post is done. You can try Memory Cache Hub by following the installation instructions in the README.

My goal for Memory Cache Hub was just to get the project to this point. It was useful to build and I learned a lot, but there are no plans to continue development.

For the rest of this post, I would like to share some thoughts/takeaways from working on the project.

- Client/Server architecture is convenient, especially with OpenAPI specs.

- Browser clients are great until they’re not.

- Llamafiles are relatively painless.

- Python and PyInstaller pros/cons.

- Github Actions and large files.

- There’s a lot of regular (non-AI) work that needs doing.

The Client / Server Architecture is convenient, especially with OpenAPI specs.

This is probably a boring point to start with, and it’s old news. Still, I thought it’d be worth mentioning a couple of ways that it turned out to be nice to have the main guts of the application implemented behind an HTTP server.

When I was testing out llamafiles, I wanted to try enabling GPU acceleration, but my main development machine had some compatibility issues. Since Memory Cache was built as a separate client/server, I could just run the server on another machine (with a compatible GPU) and run the client on my main development machine. It was super painless.

We built Memory Cache with on-device AI in mind, but another form that could make sense is to run AI workloads on a dedicated homelab server (e.g. “an Xbox for AI”) or in a private cloud. If the AI apps expose everything over HTTP apis, it’s easy to play around with these kinds of setups.

Another time I was glad to have the server implemented separately from the client was when I wanted to build an emacs plugin that leveraged RAG + LLMs for my programming projects. I wrote about the project on my blog. As I was building the plugin I realized that I could probably just plug in to Memory Cache Hub instead of building another RAG/LLM app. It ended up working great!

Unfortunately, I stopped working on the emacs plugin and left it in an unfinished state, mostly because I couldn’t generate elisp client code for Memory Cache Hub’s Open API spec. By the way, if anyone wants to write an elisp generator for Open API, that would be really great!

I ended up generating typescript code from the OpenAPI spec for use in the Memory Cache Browser Client. The relevant bit of code was this:

# Download the openapi.json spec from the server

curl http://localhost:4444/openapi.json > $PROJECT_ROOT/openapi.json

# Generate typescript code

yarn openapi-generator-cli generate -i $PROJECT_ROOT/openapi.json -g typescript-fetch -o $PROJECT_ROOT/src/api/

Browser Clients Are Great, Until They’re Not

I am familiar with web front end tools – React, javascript, parcel, css, canvas, etc. So, I liked the idea of building a front end for Memory Cache in the browser. No need to bundle things with electron, and no need to train other developers I might be working with (who were also mostly familiar with web development).

For the most part, this worked out great. While the UI isn’t “beautiful” or “breathtaking” – it was painless and quick to build and it’d be easy for someone who really cared about it to come in and improve things.

That said, there were a couple of areas where working in the browser was pretty frustrating:

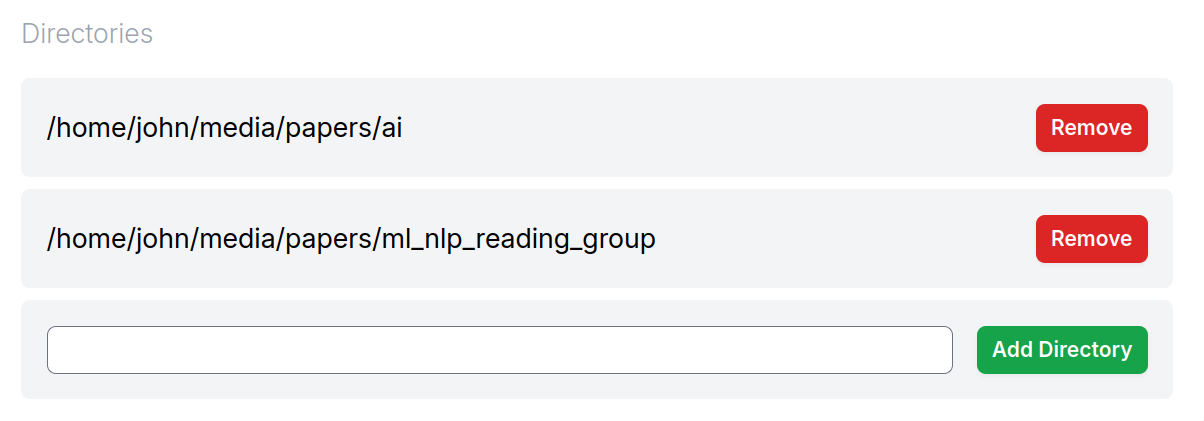

- You can’t specify directories via a file picker.

- You can’t directly send the user to a file URL.

No file picker for me

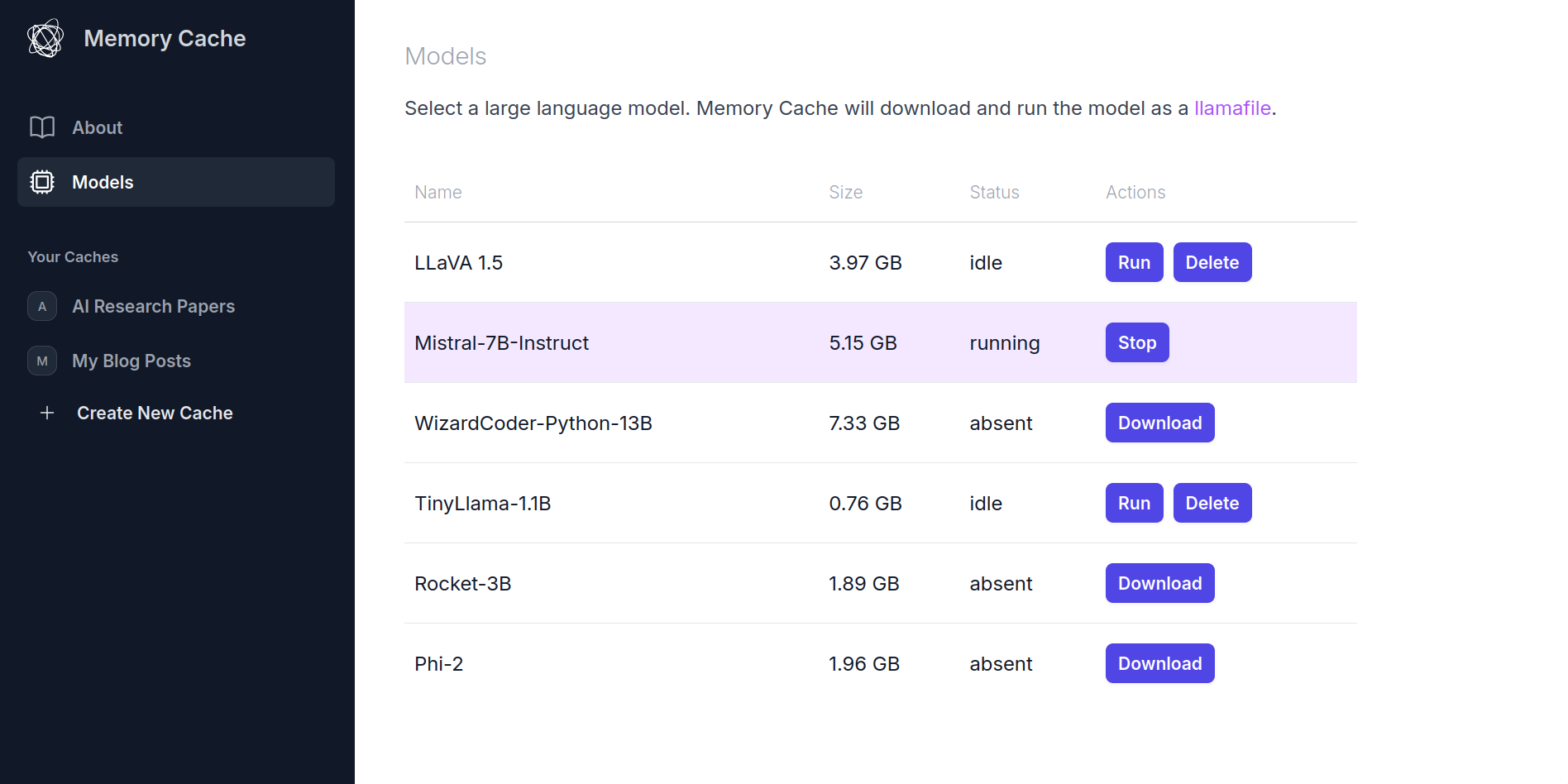

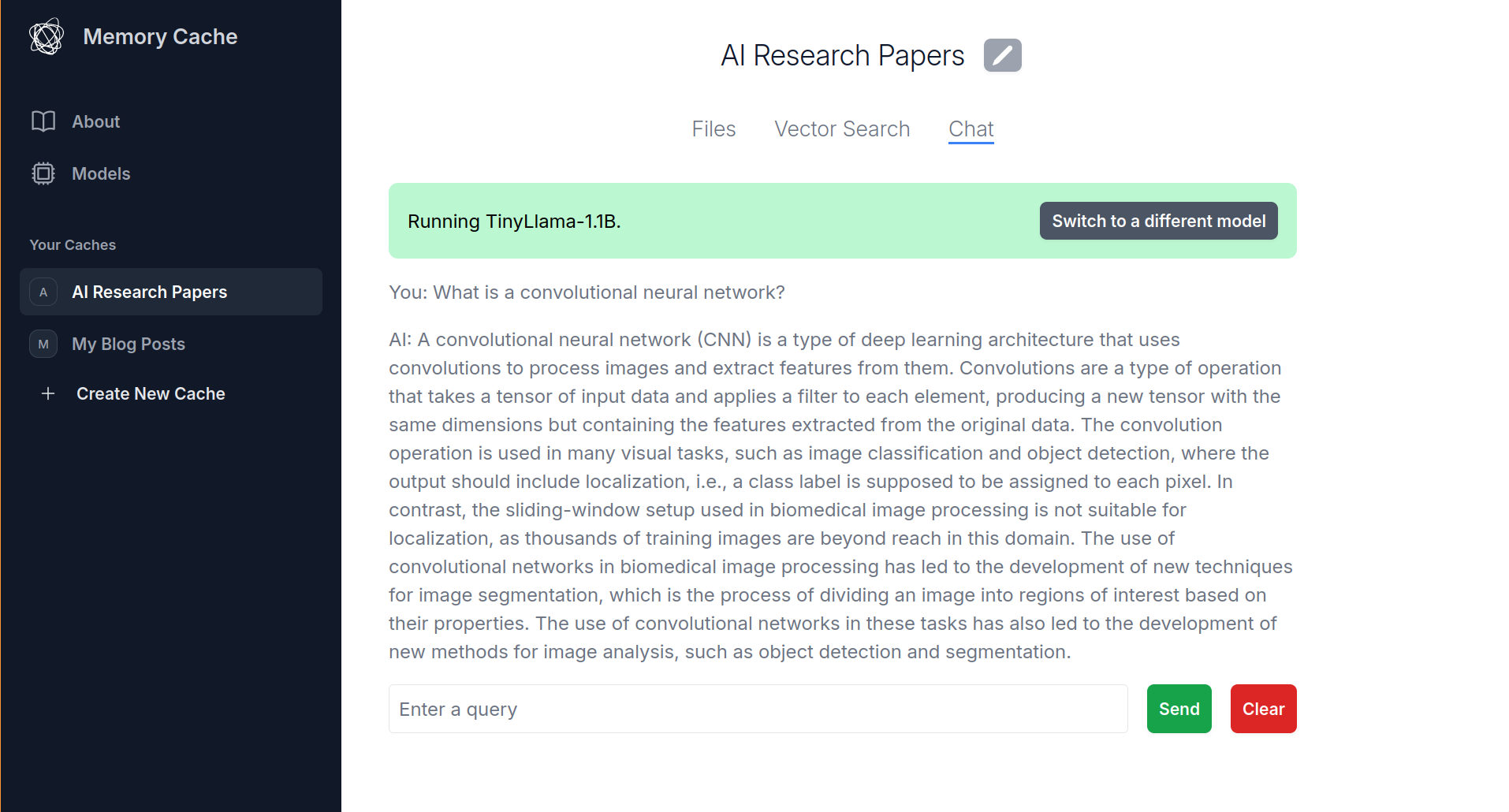

The way Memory Cache works is that the user specifies files in their filesystem that they want to add to their “cache”s. The server will make its own copies of the files in those directories for ingestion and such. The problem is that while browsers have built-in support for a file upload window, there’s no way to tell the browser that we want the user to specify full paths to directories on their hard drive.

It’s not surprising that browser’s don’t support this. This isn’t really what they’re made for. But it means that for this initial version of Memory Cache Hub, I settled for telling the user to type complete file paths into an input field rather than having a file picker UI. This feels really bad and particularly unpolished, even for a demo app.

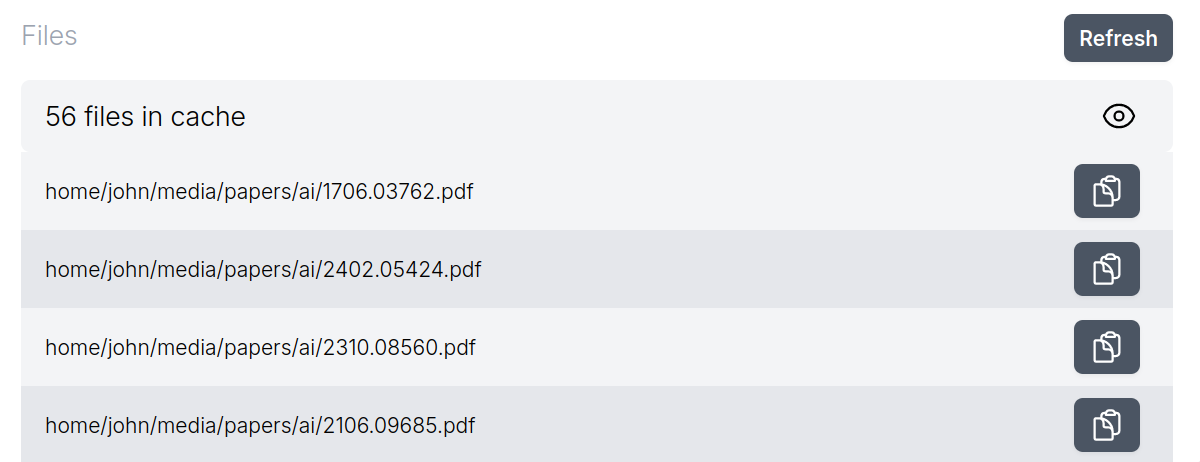

No file previews

The browser acts as a file viewer if you specify the path of a file prefixed with file:// in the address bar. This is convenient, because I wanted to let users easily view the files in their cache.

Unfortunately, due to security concerns, the browser disallows redirects to file:// links. This means that the best I could do for Memory Cache was provide a “copy” button that puts the file:// URI onto the user’s clipboard. Then, they can open a new tab, paste the URL and preview the file. This is a much worse experience.

My client could also have provided file previews (e.g. of PDF’s) directly with the server sending the file contents to the client, but I didn’t end up going down this route.

Again, this isn’t surprising because I’m mostly using the browser as an application UI toolkit and that’s not really what it’s for. Electron (or something like it) would have been a better choice here.

Llamafiles are (relatively) painless

Using llamafiles for inference turned out to be an easy win. The dependencies of my python application stayed pretty simple because I didn’t need to bring in hugging face / pytorch dependencies (and further separate platforms along CUDA/ROCm/CPU boundaries).

There are some “gotchas” with using llamafiles, most of which are documented in the llamafile README. For example, I don’t end up enabling GPU support because I didn’t spend time on handling errors that can occur if llamafile fails to move model weights to GPU for whatever reason. There are also still some platform-specific troubleshooting tips you need to follow if the llamafile server fails to start for whatever reason.

Still, my overall feeling was that this was a pretty nice way to bundle an inference server with an application, and I hope to see more models bundled as llamafiles in the future.

Python and PyInstaller Pros and Cons

I’m not very deeply embedded in the Python world, so figuring out how people built end-user programs with Python was new to me. For example, I know that Blender has a lot of python code, but as far as I can tell, the core is built with C and C++.

I found PyInstaller and had success building standalone executables with it (as described in this previous blog post and this one too).

It worked, which is great. But there were some hurdles and downsides.

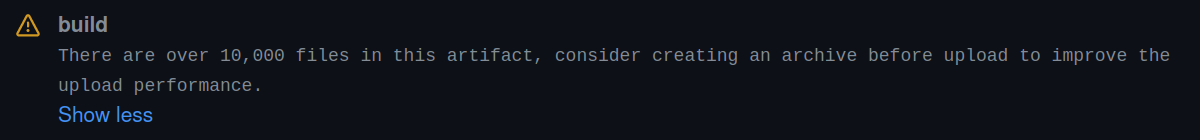

The first complaint is about the way single-file builds work. At startup, they need to unpack the supporting files. In our case, we had something like ~10,000 supporting files (which is probably our fault, not PyInstallers) that get unpacked to a temporary directory. This takes ~30 seconds of basically just waiting around with no progress indicator or anything else of that nature. PyInstaller has an experimental feature for adding a splash screen, but I didn’t end up trying it out because of the disclaimer at the top explaining that the feature doesn’t work on MacOS. So, the single-file executable version of Memory Cache Hub appears as if it hangs for 30 seconds when you start it before eventually finishing the unpacking process.

The second complaint is not really about PyInstaller and more about using Python at all, which is that in the end we’re still running a python interpreter at runtime. There’s no real “compile to bytecode/machine code” (except for those dependencies written in something like Cython). It seems like python is the most well-supported ecosystem for developer tools for ML / AI, and part of me wishes I were spending my time in C or Rust. Not that I’m excellent with those languages, but considering that I get better at whatever I spend time doing, I’d rather be getting better at things that give me more control over what the computer is actually doing.

Nothing is stopping me from choosing different tools for my next project, and after all - llama.cpp is pretty darn popular and I’m looking forward to trying the (rust-based) burn project.

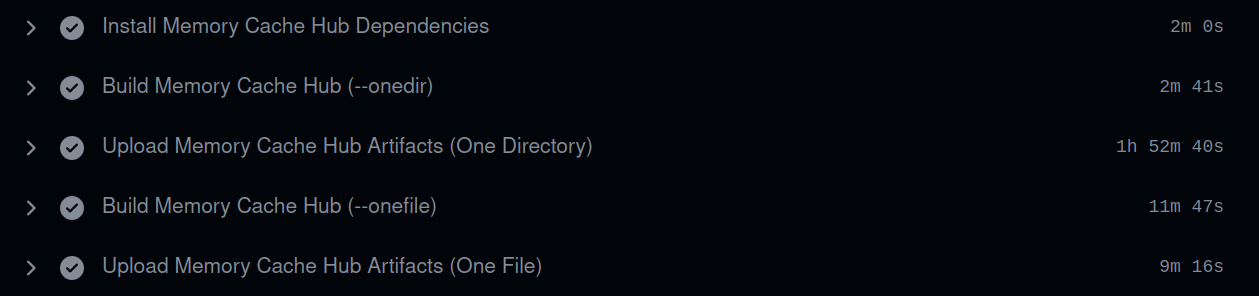

Github Actions and Large Files

Ok, so here’s another problem with my gigantic bundled python executables with 10,000 files… My build pipeline takes 2+ hours to finish!

Uploading the build artifacts from the runner to github takes a long time – especially for the zips that have over 10,000 files in them. This feels pretty terrible. Again, I think the problem is not with Github or PyInstaller or anything like that – The problem is thinking that shipping 10,000 files was a good idea. It wasn’t – I regret it. haha.

There’s a lot of non-AI work to be done

90% of the effort I put into this project was completely unrelated to AI, machine learning, rag, etc. It was all, “How do I build a python server”, “How do we want this browser client to work?”, “What’s PyInstaller?”, “How do we set up Github Actions?” etc.

The idea was that once we had all of this ground work out of the way, we’d have a (user-facing) playground to experiment with whatever AI stuff we wanted. That’s all fine and good, but I’m not sure how much time we’re going to actually spend in that experiment phase, since in the meantime, there have been many other projects vying for our attention.

My thoughts about this at the moment are two fold.

First, if your main goal is to experiment and learn something about AI or ML – Don’t bother trying to wrap it in an end-user application. Just write your python program or Jupyter notebook or whatever and do the learning. Don’t worry if it doesn’t work on other platforms or only supports whatever kind of GPU you happen to be running – none of that changes the math / AI / deep learning / ML stuff that you were actually interested in. All of that other stuff is a distraction if all you wanted was the core thing.

However – if your goal is to experiment with an AI or ML thing that you want people to use – Then get those people on board using your thing as fast as possible, even if that means getting on a call with that, having them share their desktop and following your instructions to set up a python environment. Whatever you need to do to get them actually running your code and using your thing and giving you feedback – that’s the hurdle you should cross. That doesn’t mean you have to ship out to the whole world. Maybe you know your thing is not ready for that. But if you have a particular user in mind and you want them involved and giving you constant feedback, it’s good to bring them in early.

What Now?

Learning the build / deploy side of things was pretty helpful and useful. I’d never built a python application like this one before, and I enjoyed myself along the way.

There’s been some interest in connecting Memory Cache more directly with the browser history, with Slack, with emails, and other document/information sources. That direction is probably pretty useful – and a lot of other people are exploring that space too.

However, I’ll likely leave that to others. My next projects will be unrelated to Memory Cache. There are a lot of simple ideas I want to play around with in the space just to deepen my understanding of LLMs, and there are a lot of projects external to Mozilla that I’d like to learn more about and maybe contribute to.

Screenshots