Memory Cache Dev Log March 7 2024

Author: John Shaughnessy

Memory Cache Dev Log, March 7 2024

A couple months ago we introduced Memory Cache:

Memory Cache, a Mozilla Innovation Project, is an early exploration project that augments an on-device, personal model with local files saved from the browser to reflect a more personalized and tailored experience through the lens of privacy and agency

Since then we’ve been quiet…. too quiet.

New phone, who dis?

It’s my first time writing on this blog, so I want to introduce myself. My name is John Shaughnessy. I’m a software engineer at Mozilla.

I got involved in Memory Cache a few months ago by resolving an issue that was added to the github repo and a couple weeks ago I started building Memory Cache V2.

Why V2?

Memory Cache V1 was a browser extension and that made it convenient to collect and feed documents to an LLM-based program called privateGPT. PrivateGPT would break the documents into fragments, save those fragments in a vector database, and let you perform similarity search on those documents via a command line interface. We were running an old version of PrivateGPT based on LangChain.

There were several big, obvious technical gaps between Memory Cache V1 and what we’d need in order to do the kind of investigative research and product development we wanted to do.

It seemed to me that if we really wanted to explore the design space, we’d need to roll our own backend and ship a friendly client UI alongside it. We’d need to speed up inference and we’d need more control over how it ingested documents, inserted context, batched background tasks and presented information to you.

We also needed to fix the “getting started” experience. Setting up V1 required users to be comfortable working on the command line, managing python environments, and in general understanding their file system. As far as I’m aware, there are only three of us who have gone through the steps to actually set up and run V1. We were inspired by Llamafile and cosmopolitan, which create executables that you just download and run on many platforms.

And lastly, we’re excited about multiplayer opportunities. Could insights that my LLM generates become useful to my teammates? Under what circumstances would I want to share my data with others? How should I separate what’s private, semi-private, or public?

Running LLMs for Inference

I wasn’t very familiar with running LLMs, and I certainly hadn’t written an application that did “Retrieval-Augmented Generation” (RAG), which was what we wanted Memory Cache to do. So I started down a long, winding path.

Liv and I chatted with Iván Martínez who wrote privateGPT. He was super helpful! And it was exciting to talk to someone who’d built something that let us prototype what we wanted to do so quickly.

Mozilla had just announced Llamafile, which seemed like a great way to package an LLM and serve it on many platforms. I wasn’t familiar with either Llama.cpp or cosmo, so there was a lot to learn. Justine and Stephen were incredibly helpful and generous with their time. I didn’t contribute much back to the project other than trying to write accurate reports of a couple issues (#214, #232) I ran into along the way.

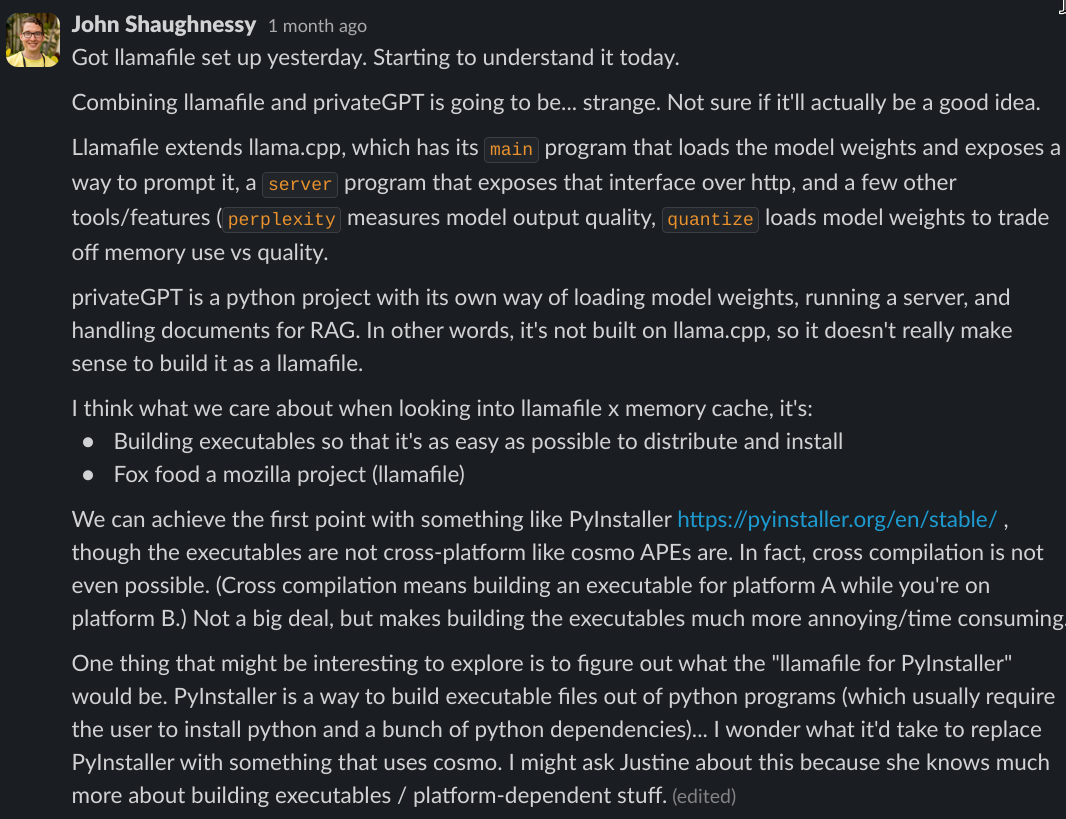

Initially when I was looking into Llamafile, I wanted to repackage privateGPT as a Llamafile so that we could distribute it as a standalone executable. Eventually realized this wasn’t a good idea. Llamafile bundles Llama.cpp programs as executables. Cosmopolitan can also bundle things like a python interpreter, but tracking down platform-specific dependencies of privateGPT and handling them in a way that was compatible with cosmo was not going to be straightforward. It’s just not what the project was designed to do.

Once I worked through the issues I was having with my GPU, I was amazed and excited to see how fast LLMs can run. I made a short comparison video that shows the difference: llamafile CPU vs GPU.

I thought I might extend the simple HTTP server that’s baked into Llamafile with all the capabilities we’d want in Memory Cache. Justine helped me get some “hello world” programs up and running, and I started reading some examples of C++ servers. I’m not much of a C++ programmer, and I was not feeling very confident that this was the direction I really wanted to go.

I like working in Rust, and I knew that Rust had some kind of story for getting C and C++ binding working, so I wrote a kind of LLM “hello world” program using rustformers/llm. But after about a week of fiddling with Llamafile, Llama.cpp, and rustformers, I felt like I was going down a bit of a rabbit hole, and I wanted to pull myself back up to the problem at hand.

Langchain and Langserve

Ok. So if we weren’t going to build out a C++ or Rust server, what should we be doing? PrivateGPT was a python project, and the basic functionality was similar to what I’d done in some simple programs I’d written with hugging face’s transformers library. (I mentioned these in a blog post and talk about upskilling in AI.)

It seemed like LangChain and LlamaIndex were the two popular python libraries / frameworks for building RAG apps, so I wrote a “hello world” with LangChain. It was… fine. But it seemed like a lot more functionality (and abstraction, complexity, and code) than I wanted.

I ended up dropping the framework after reading the docs for ChromaDB and FastAPI.

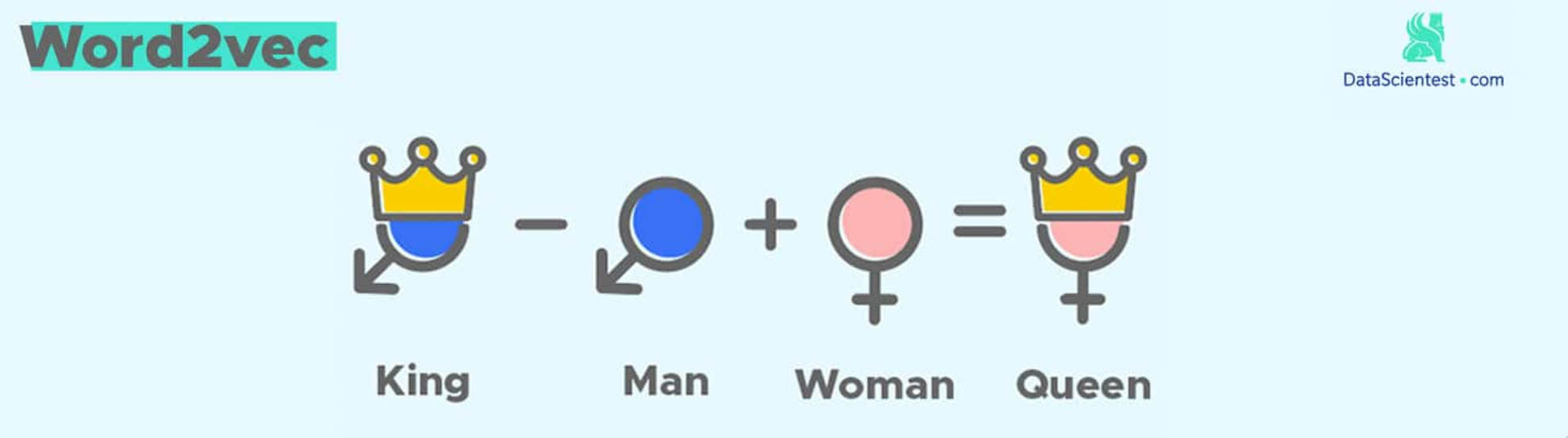

ChromaDB is a vector database for turning documents into fragments and then run similarity search (the fundamentals of a RAG system).

I needed to choose a database, and I chose this one arbitrarily. Langchain had an official “integration” for Chroma, but I felt like Chroma was so simple that I couldn’t imagine an “integration” being helpful.

FastAPI is a python library for setting up http servers, and is “batteries included” in some very convenient ways:

- It’s compatible with pydantic which lets you define types, validate user input against them, and generate

OpenAPIspec from them. - It comes with swagger-ui which gives an interactive browser interface to your APIs.

- It’s compatible with a bunch of other random helpful things like python-multipart.

The other thing to know about

FastAPIis that as far as http libraries go, it’s very easy to use. I was reading documentation aboutLangserve, which seemed like a kind of fancy server forLangchainapps until I realized that actuallyFastAPI,pydantic,swagger-uiet. al were doing all the heavy lifting.

So, I dropped LangChain and Langserve and decided I’d wait until I encountered an actually hard problem before picking up another framework. (And who knows – such a problem might be right around the corner!)

It helped to read LangChain docs and code to figure out what RAG even is. After that I was able to get basic rag app working (without the framework). I felt pretty good about it.

Inference

I still needed to decide how to run the LLM. I had explored Llamafiles and Hugging face’s transformers library. The other popular option seemed to be ollama, so I gave that a shot.

Ollama ended up being very easy to get up and running. I don’t know very much about the project. So far I’m a fan. But I didn’t want users of Memory Cache to have to download and run an LLM inference server/process by themselves. It just feels like a very clunky user experience. I want to distribute ONE executable that does everything.

Maybe I’m out of the loop, but I didn’t feel very good about any of the options. Like, what I really wanted was to write a python program that handled RAG, project files, and generating various artifacts by talking to an llm, and I also wanted it to run the LLM, and I also wanted it to be an HTTP server to serve a browser client. I suppose that’s a complex list of requirements, but it seemed like a reasonable approach for Memory Cache. And I didn’t find any examples of people doing this.

I had the idea of using Llamafiles for inference and a python web server for the rest of the “brains”, which could also serve a static client. That way, the python code stays simple (it doesn’t bring with it any of the transformers / hugging face / llm / cuda code).

Memory Cache Hub

I did a series of short spikes to piece together exactly how such an app could work. I wrote a bit about each one in this PR.

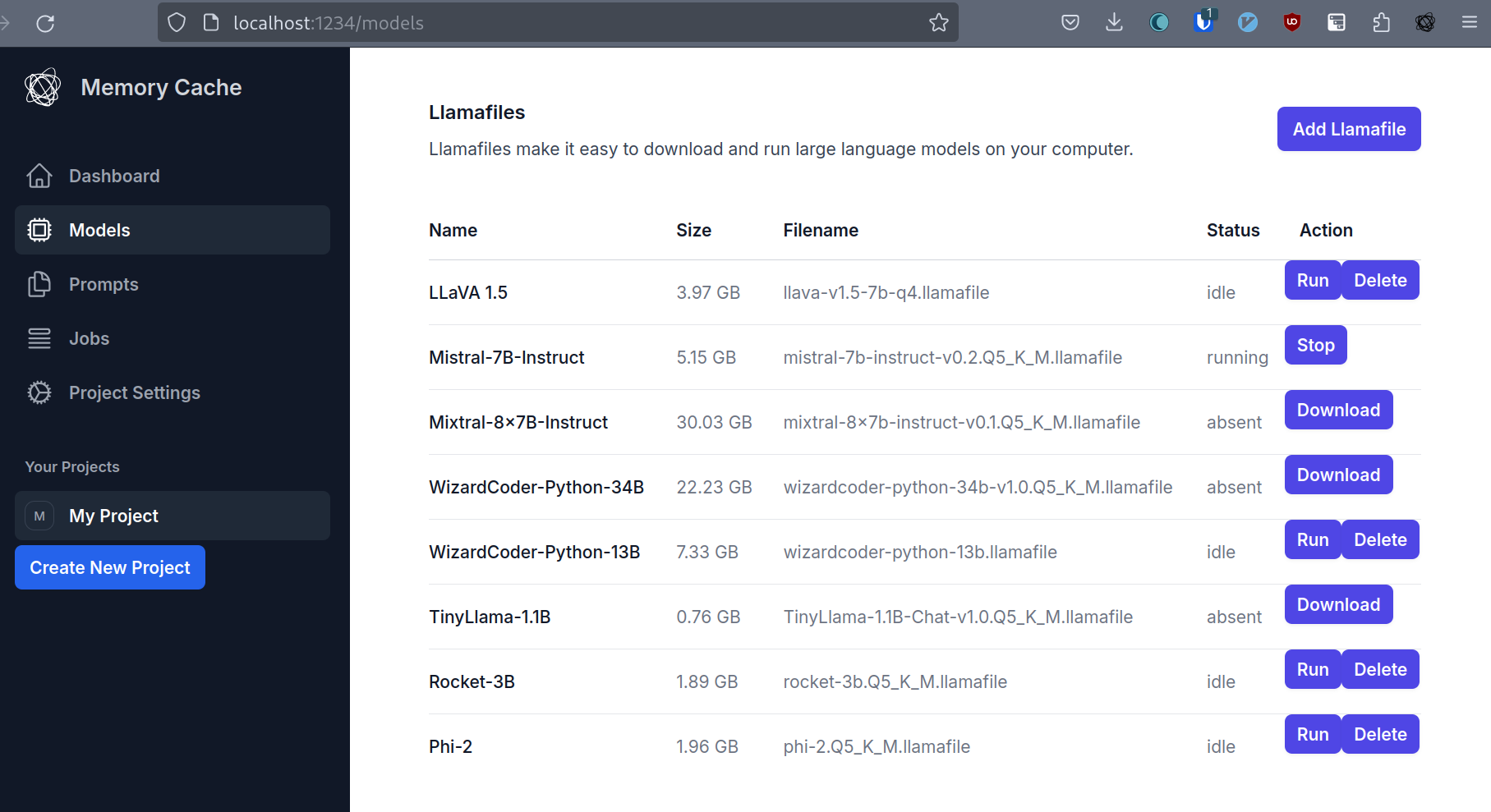

In the end, I landed on a (technical) design that I’m pretty happy with. I’m putting the pieces together in a repo called Memory Cache Hub (which will graduate to the Mozilla-Ocho org when it’s ready). The README.md has more details, but here’s the high level:

Memory Cache Hub is a core component of Memory Cache:

- It exposes APIs used by the browser extension, browser client, and plugins.

- It serves static files including the browser client and various project artifacts.

- It downloads and runs llamafiles as subprocesses.

- It ingests and retrieves document fragments with the help of a vector database.

- It generates various artifacts using prompt templates and large language models.

Memory Cache Hub is designed to run on your own machine. All of your data is stored locally and is never uploaded to any server.

To use Memory Cache Hub:

- Download the latest release for your platform (Windows, MacOS, or GNU/Linux)

- Run the release executable. It will open a new tab in your browser showing the Memory Cache GUI.

- If the GUI does not open automatically, you can navigate to http://localhost:4444 in your browser.

Each release build of Memory Cache Hub is a standalone executable that includes the browser client and all necessary assets. By "standalone", we mean that you do not need to install any additional software to use Memory Cache.

A Firefox browser extension for Memory Cache that extends its functionality is also available. More information can be found in the main Memory Cache repository.

There are two key ideas here:

- Inference is provided by llamafiles that the hub downloads and runs.

- We use

PyInstallerto bundle the hub and the browser client into a single executable that we can release.

The rest of the requirements are handled easily in python because of the great libraries and tools that are available (fastapi, pydantic, chromadb, etc).

Getting the two novel ideas to work was challenging. I’m not a python expert, so figuring out the asyncio and subprocess stuff to download and run llamafiles was tricky. And PyInstaller has a long list of “gotchas” and “beware” warnings in its docs. I’m still not convinced I’m using it correctly, even though the executables I’m producing seem like they’re doing the right thing.

The Front End

By this time I had built three measly, unimpressive browser clients for Memory Cache. The first was compatible with privateGPT, the second was compatible with some early versions of the Memory Cache Hub. I built the third with gradio but quickly decided that it did not spark joy.

And none of these felt like good starting points for a designer to jump into the building process.

I’ve started working on a kind of “hello world” dashboard for Memory Cache using tailwindcss. I want to avoid reinventing the wheel and make sure the basic interactions feel good.

I’ve exposed most of the Hub’s APIs in the client interface by now. It doesn’t look or feel good yet, but it’s good to have the basic capabilities working.

What We’re Aiming For

The technical pieces have started to fall into place. We’re aiming to have the next iteration of Memory Cache - one that you can easily download and run on your own machine - in a matter of weeks. In an ideal world, we’d ship by the end of Q1, which is a few weeks away.

It won’t be perfect, but it’ll be far enough along that the feedback we get will be much more valuable, and will help shape the next steps.